Networked USB Flash Drive

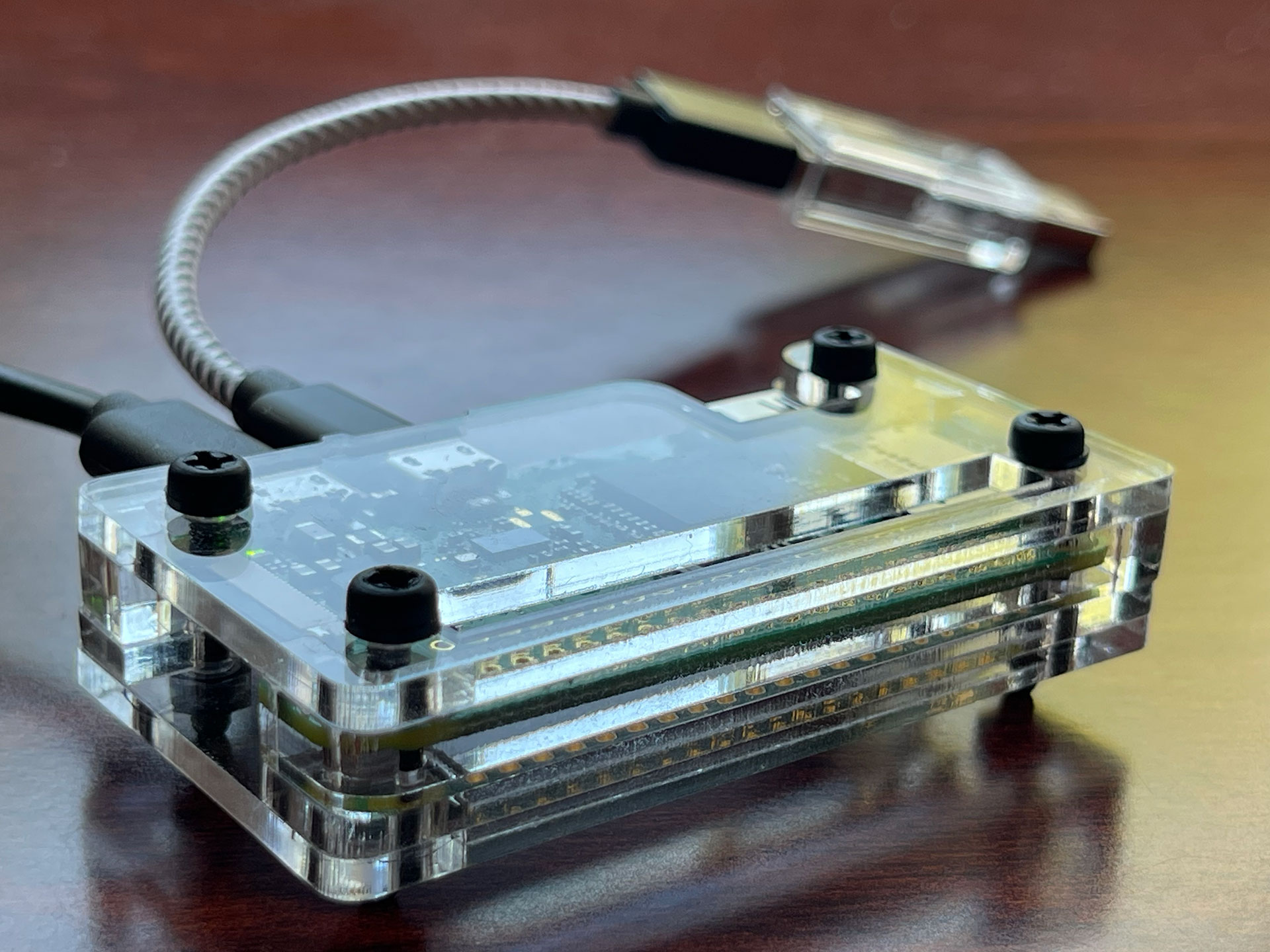

I turned a Raspberry Pi I had sitting around into a network-connected USB flash drive with a custom fabricated clear acrylic case.

Continue readingI turned a Raspberry Pi I had sitting around into a network-connected USB flash drive with a custom fabricated clear acrylic case.

Continue readingCutting paper in the laser can be challenging. The stock has to be held down uniformly across the surface, particularly if you are cutting small pieces out entirely. Otherwise, the air assist can move the cut-out bits around and, they can interfere with other cuts.

I mostly have been using Seklema hold-down mats for this. They have a sticky gel layer that holds the paper down without transferring any residue. They work really well but, they ablate with use and, are a bit expensive.

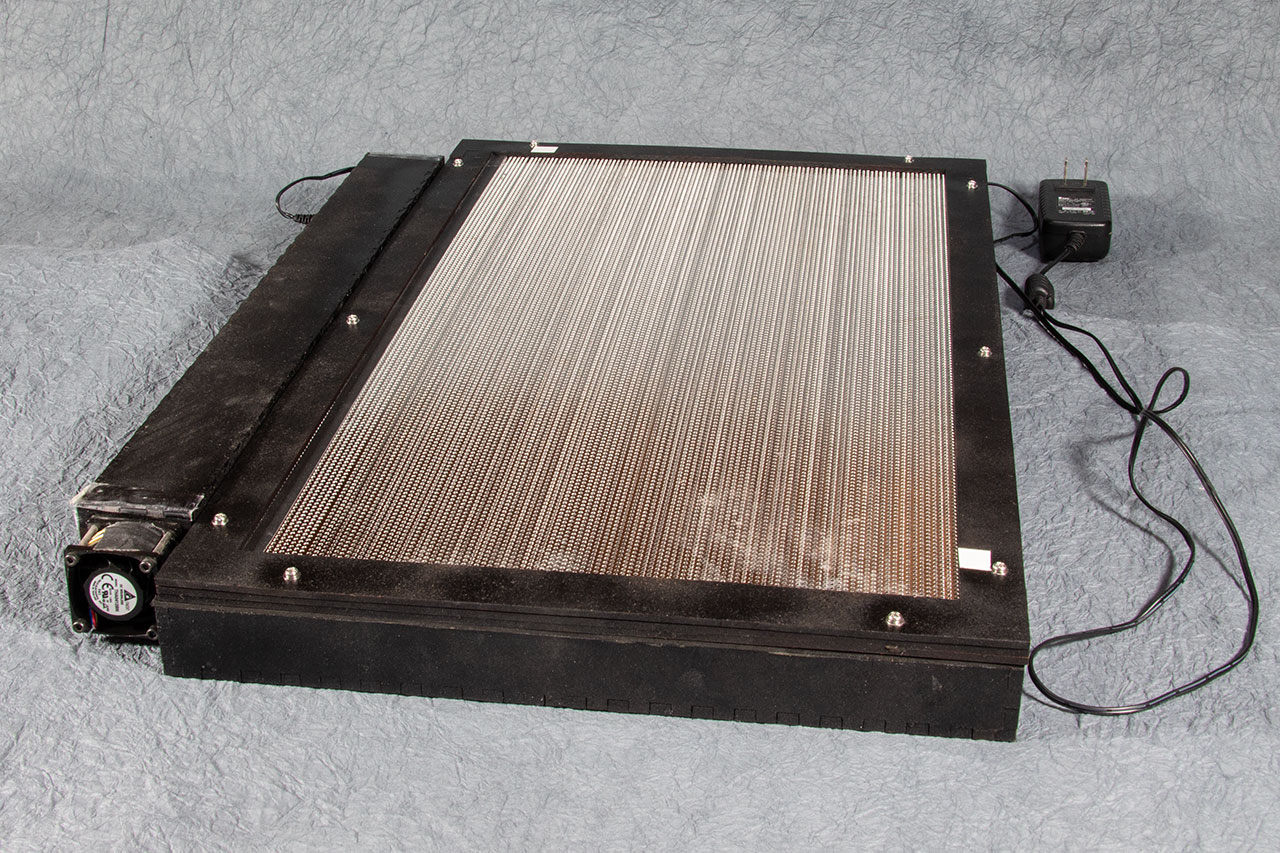

With some laser cutters, you can get a vacuum tray that holds lightweight materials like paper down with controlled airflow. There isn’t one of those for the Glowforge. So, I made my own.

This is heavily inspired by several other vacuum trays made by other Glowforge owners in this forum thread.

I designed this in Inkscape. I used a tabbed box generator for the two main bodies: the tray and the fan box. I modified the output to break the pieces into sizes I can cut in the Glowforge and, to add additional features like holes for the fan and electronics and channels for air flow.

The tray is 1/4” thick MDF. I lined the bottom with aluminum foil for extra protection in case any stray lasering gets through. It’s probably overkill but, I sealed the seams with silicone caulk to reduce air leaks. The cutting surface is a piece of perforated stainless steel plate sandwiched in an MDF frame. That is held down to the rest of the tray using magnets, with an EVA foam gasket to help with air leaks.

The fan box is 1/8” thick MDF with press-fit holes for the power connector and switch. The fan is bolted on to the end opposite the switch. This uses a 12v fan and a standard 12v power supply. The cord hangs out through the front of the lid of the machine.

I painted all the MDF black so it would look more finished and less cobbled together.

Cutting the plate steel without access to a shear was a new adventure for me but, worked out really well.

It works great, as you can see in the 1.6-minute demo video below.

Experimenting with powder-coat-filled laser engraves on the Glowforge.

Continue readingI played with some green screen chromakey stuff for video last year. It’s a bit fiddly to get the screen and the subject lit right for it to work well.

I was excited to learn that it was possible to get better results with a retroreflective screen and a colored light ring. The general idea is that the fabric reflects the light back in the same direction from which it came. By shining even a relatively dim colored light at the screen from right around the camera lens, you get an almost perfectly-even colored background. It is much less sensitive to the subject’s distance from the screen, etc.

John Park posted a project write-up with his plan for building an appropriate light ring a few months ago. It looked pretty straight-forward. So, I gave it a go. My 3D printer is not large enough to print his mount design in one piece and, I didn’t really want to mess with printing in sections for assembly. Instead, I did a quick (and pretty sloppy) adaptation of the design in lasercut acrylic. The LED ring sits in a channel made with a bunch of little L brackets, glued on with acrylic solvent. Similarly, the grippers are several layers of acrylic glued together.

The electronics design and code are all straight from John Park’s project.

This works really well! Light spill on the background from lighting the subject can still be a problem. I was able to adjust settings for the chroma and luma range in post to compensate where I had issues pretty easily, though. In later attempts, I was more careful about where I pointed my lights.

It is not clear from the photos but, it is better to get the screen as flat as possible. It works with a little wrinkling but, it makes the light spill issue more likely. I tightened the screen to the frame a bit more for later attempts.

It is also worth noting that the retroreflective fabric bruises pretty easily after its protective film comes off.

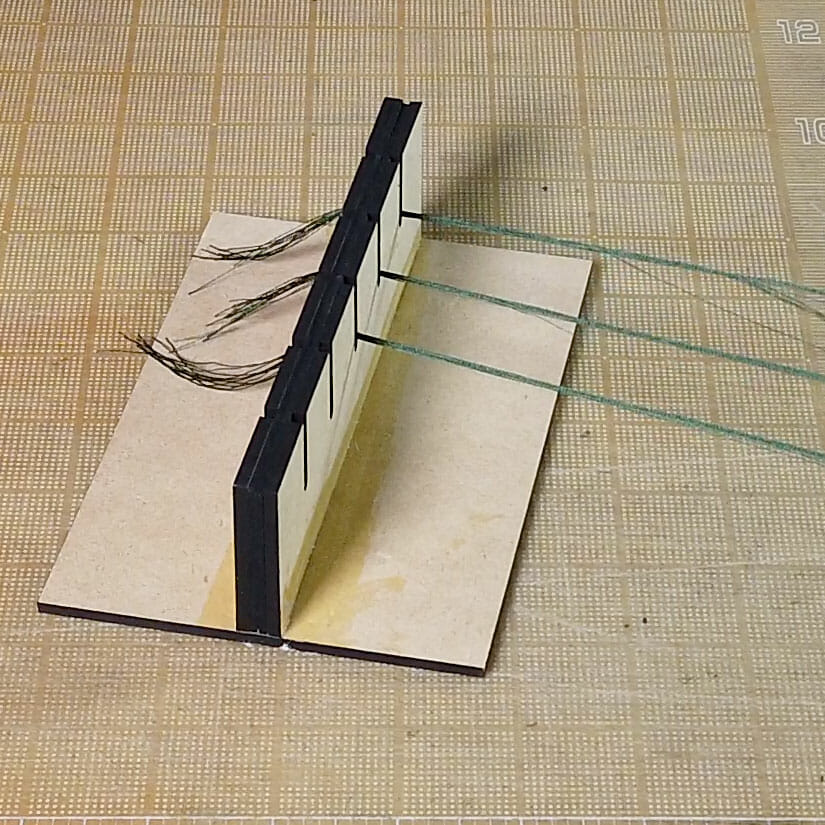

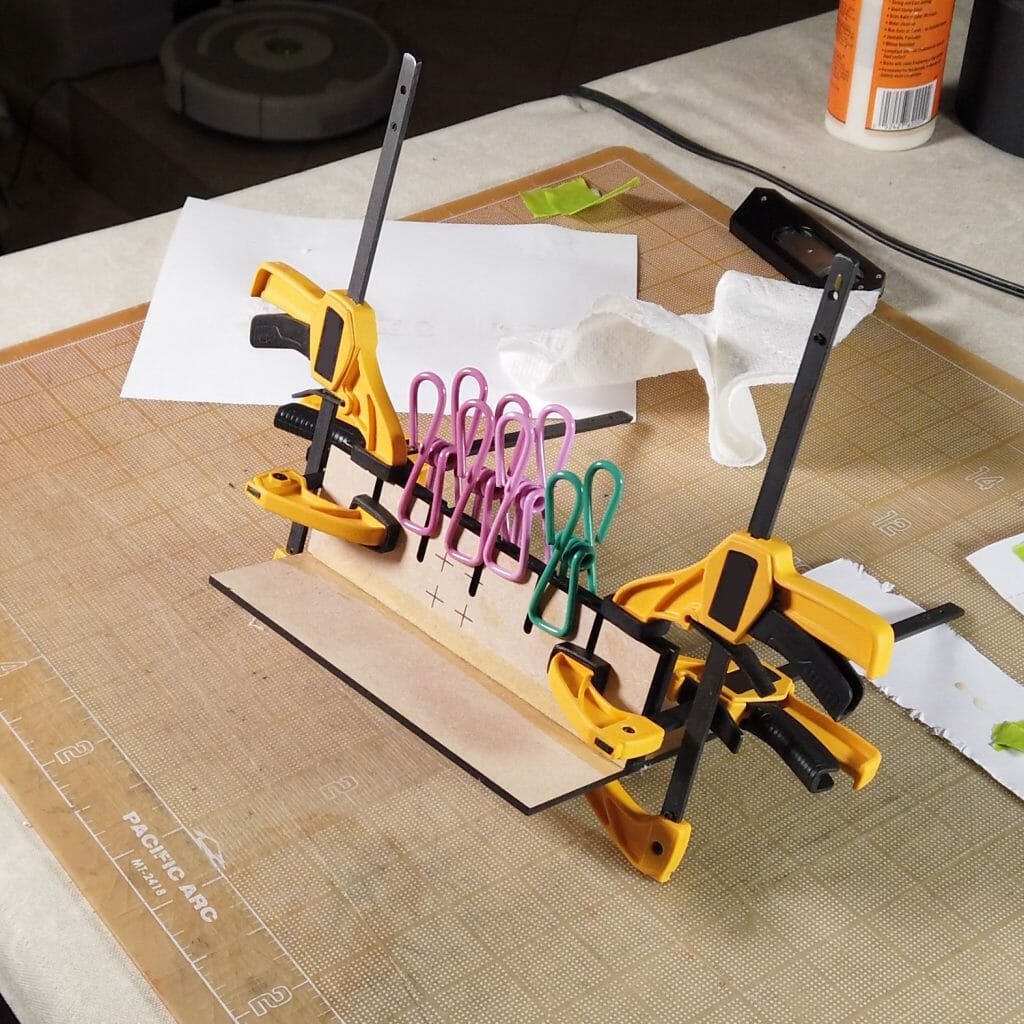

This is a quick, simple tool to assist when separating skeins of kumihimo (or embroidery) floss into working clusters with the desired number of strands. The upright is a sandwich of a piece of EVA foam between two pieces of 1/4″ stock (MDF here but, something like Baltic birch ply or acrylic should work, too). The EVA is sliced with a razor blade in the middle of each channel. Then, just glue it all together with wood glue. Some clamping is likely required while it dries.

It is probably best to clamp it down to a table when using. Knot the end of the skein/bundle of strands and, slip it into the cut in the EVA. That should keep the end in place while you separate the full length.

These files are for personal, non-commercial use only. Note that, by referencing these, you are agreeing to release any variations you create under identical terms.

My first attempt at saddle stitching on a project made the value of a stitching pony immediately clear to me for that. They also seem to be pretty useful for softly clamping other small things on which one is working. Commercially-made stitching ponies are not particularly expensive or hard to find. I was thinking about the springiness of plywood and, how easy it might be to make something with a simple cam clamp. I gave it a try and, this worked out even better than I expected. I was actually a bit sloppy building this because I assumed it was going to be a prototype I threw away. It works great and, seems to be everything I need for now, though.

These files are for personal, non-commercial use only. If you want to produce these to sell or for other business use, please contact me to arrange for licensing terms. Also note that, by referencing these, you are agreeing to release any variations you create under identical terms.

You could cut this with a scroll saw, jig saw or hack saw pretty easily. Of course, if you don’t have one and, really want your own laser, feel free to use my Glowforge referral code to purchase your own. Glowforge will give you a discount off their posted price and, I will get a credit kickback to help defray the cost of materials for future projects. Your support is always appreciated.

You are almost certainly better off buying your Baltic birch plywood from a local supplier. You can get little boxes of it online but, it is generally twice the price.

1/4″ Baltic Birch Plywood (Amazon)

1/8″ Baltic Birch Plywood (Amazon)

1/4″ Baltic Birch Plywood (Woodworkers Source)

Here is the cam clamp I used. Anything similar should work. This uses a standard quarter-twenty bolt. So, it should be possible to replace with a longer one, if desired.

I used this leather because it was handy but, any soft vegetable-tanned medium-weight leather should work.

Medium Natural Leather (Glowforge)

Table Vise (Amazon) if you don’t already have one.

Of course, you can also just buy a stitching pony for a similar amount:

Note that I am not recommending that particular stitching pony. I haven’t tried it. I am just pointing out that you can buy one ready-made.

Amazon referral links for some parts and incidentals defray IT and hosting costs for a local arts organization (Arizona Aikido).

The Blacktooth Laser Cutter is a laudable experiment in producing a low-cost laser cutter and engraver from a time when commercial options were mostly over $15K USD, despite the cost of the component technologies having come way down. A significant amount of adjustment and modification is necessary to make the Blacktooth serviceable for any particular application. For those with a strong DIY ethos who enjoy tinkering with their equipment, it is likely still a solid option for a small shop or maker space. For most people looking for a laser to use as a general purpose shop or studio tool, there are now options requiring less tinkering and, with a shallower learning curve.

Update: I handed the Blacktooth laser off to a local school with a nascent maker space in 2019. In addition to a very competent teacher supervising the project, they have a literal rocket scientist available to assist.

The Blacktooth laser started as a Kickstarter campaign in October of 2012 [1]. Behind it was a team that was already building other affordable CNC equipment, BuildYourCNC [2]. The Kickstarter campaign failed to get enough support but, they decided to proceed with the project and, generously, to honor the price offered to backers during the campaign.

So, in April of 2013, my factory-assembled Blacktooth Laser Cutter arrived, well-wrapped, on a large wooden palette. Getting it set up and in any way operational took me awhile.

The documentation for the Blacktooth is basically the assembly instructions [3] and, whatever you can glean from the support forums. Mine required an additional shipment of fasteners and, a few exchanges with support to understand what was part of the machine assembly and, what was for protection during shipping.

It is important to note that the DIY ethos runs very deep in the community of people using the Blacktooth. It quickly became clear from exchanges in the forums that no two users really have the same machine. Everyone has modified their Blacktooth significantly from the original design.Typical changes include homing limit switches, which make it easier to set the origin point and avoid driving the laser head beyond its actual range; upgraded air assist; filtration systems and digital signal processors (DSP).

BuildYourCNC was enthusiastic and quick to respond to my support inquiries. There were some initial issues where the employee helping me left the company, stopped responding and, no one took over monitoring their email address. They may need a support ticketing system. I noted that they were guarded or vague about some topics (like exhaust filtration and venting, safety equipment, etc.), presumably for liability reasons. Most of the responses I got from BuildYourCNC support were along the lines of a starting place to figure it out rather than a complete solution.

Most commercial laser cutters have a component called a digital signal processor or DSP. The DSP is a sort of purpose-built computer that takes input in a standard format (typically raster and vector image formats) and, converts them into the signals that control the movement of the laser cutter. In most cases, this allows the operator to use standard image editing software and feed their jobs to the laser cutter as if it were a printer.

By contrast, the original stock Blacktooth Laser Cutter operates like a CNC machine. The movements of the laser are controlled by sending gcode (a standard CNC control language) instructions from CNC control software running on the operator’s computer. There are a number of options for this software but, one of the most common and, the one recommended for the Blacktooth is the Windows-based Mach3 [4].

There is also an opensource package that runs on Linux, predictably named LinuxCNC [5]. While I did not realize this was a workable option early on, I did later get it working with the Blacktooth. The UI is less polished but, it seemed serviceable.

Mach3 and LinuxCNC are just control software for sending gcode to the Blacktooth. To produce the the gcode for a particular design to send to the machine requires additional software. This is called computer-aided machining or CAM. I opted to work with a commercial CAM package called CamBam [6].

There are some idiosyncrasies with the Blacktooth (and any other CNC equipment, almost certainly) with regard to how specific gcode instructions are handled. Tweaking the settings in the CAM software to get the right gcode output for a particular machine can be a fiddly process. Variations in construction and the modifications people have made to their machines means that the same settings will not necessarily work the same way for anyone else.

The Blacktooth has a generous 24” by 20” cutting bed. The bottom of the case is open to allow working on larger surfaces.

In the original stock model, power is controlled by a potentiometer on the side of the case.

Cooling is provided by circulating distilled water through the tube with a pump. I set up a 5 gallon plastic bucket as the reservoir and, added an aquarium thermometer to monitor coolant temperature. This is required to avoid overheating and damaging the machine.

Another pump provides a modest “air assist,” which pushes smoke out of the way of the laser while cutting and, reduces deposition of vaporized particles on the lens.

Part of the initial set up for the Blacktooth included aligning the mirrors. This requires a fairly high level of precision. I found some descriptions of various techniques in the forums and, with a couple hours of effort, I managed to get it all working. There are a few singed spots on the interior of the enclosure but, no serious complications.

I promptly built a low dolly out of plywood for the Blacktooth. This made it possible to push it under the main workbench in the studio when not in use.

Since the bottom of the Blacktooth is open, using the wood of the dolly as a backstop for cutting with the laser seemed like a bad idea. I covered the top of the dolly with large heavy ceramic tiles. While a 40-watt CO2 laser may be able to etch into the surface finish of the tile, it won’t be able to cut through it or heat it up enough to ignite the dolly.

I also purchased a steel “honeycomb” or “egg crate” tray. These make an excellent work surface. It reduces flashback (where the laser cuts through something and, reflects off of the surface behind it to damage the back of the stock being cut) and, makes it possible to use strong magnets to hold down lighter weight stock (like paper).

I design and build a style of paper art pop up cards called origamic architecture. I had borrowed time on commercial laser cutters to produce some of my designs and, had always wanted my own laser for prototyping and production. So, I was very eager to get the Blacktooth working for that.

The gcode I was able to generate for the Blacktooth turned out to be unsuitable for cutting paper. For each vector cut, the laser would turn on. Then, the cutting head would move along the vector, stopping at the end. Then, the laser would turn off. This caused the laser to dwell at the start and end of each cut, producing a pronounced dot. While unlikely to be a serious problem on most heavier materials, this is completely unworkable for paper.

While I found other Blacktooth users who claimed to have resolved this issue, their CAM settings did not work for me. This is likely because their machines were significantly modified from the stock Blacktooth I was using.

It became clear to me that I would have to make some of these modifications to get the Blacktooth any closer to usable for my purposes.

I did experiment briefly with cutting 1/8” hardwood ply with the Blacktooth. I cut a well-charred circle at something shy of full power with multiple passes. I also etched some lines into a piece of MDF. Now that I have a little more experience working with those on other machines, I can see where masking and a different approach would likely yield better results.

I did experiment briefly with cutting 1/8” hardwood ply with the Blacktooth. I cut a well-charred circle at something shy of full power with multiple passes. I also etched some lines into a piece of MDF. Now that I have a little more experience working with those on other machines, I can see where masking and a different approach would likely yield better results.

I never tried a raster engrave on the Blacktooth. I saw some other people’s experiments and, concluded that a DSP was really the best route to getting acceptable results.

By far the most popular upgrade for Blacktooth owners is a digital signal processor (DSP). In fact, later iterations of the Blacktooth from BuildYourCNC include a DSP.

I ordered the DSP most people seemed to be using (an AWC608). I checked with BuildYourCNC for some details on wiring it in and, got back some terse preliminary notes and, a promise that they would eventually have more detailed instructions.

While I do build and repair computers and have done some electronics work, rewiring idiosyncratic devices with high voltages and fragile, high-priced components is towards the edge of my comfort zone. So, my Blacktooth is currently sitting with its un-connected DSP gathering dust.

Reading what other users were posting the forums, it became clear that an upgrade to the air assist would likely also be in my future. Typically, people replace the basic pump used for the air assist with output from a small compressor (like those used for airbrush work).

I also aspired to filtering the output rather than just venting it out a window. This turns out to be non-trivial. Commercial solutions are very pricey and, assorted DIY projects that demonstrate any acceptable level of effectiveness are involved projects.

Now that I have a working Glowforge laser cutter, it seems even less likely that I will continue working on the Blacktooth. The Glowforge made the rapid transition to a usable tool that eluded me with the Blacktooth.

Now that I am using the Glowforge regularly for assorted projects, I see where the Blacktooth could be more useful, particularly with the DSP and air assist upgrades completed. The large cutting area is appealing.

The Blacktooth is an inexpensive laser cutter that would likely be a good fit for a small maker space where it can be adapted and maintained by people who like to tinker with their tools.

If you are within reasonable driving distance of Phoenix and, the Blacktooth sounds like a good fit for you or your organization, my slightly-used Blacktooth may be looking for a better home. Drop me a note.

With the Glowforge running $2495 for a Basic unit like mine, most people who don’t need the larger bed size and, are more interested in a working tool than a tool that is easy to customize, that is likely a better option. Note that you can get an even better price ($100 to $1500 better, depending on the model) by using my referral link [7].

| Item | Required? | Price |

|---|---|---|

| Blacktooth Laser Cutter (shipped) | Y | $2200 |

| Cooling System | Y | $ 38 |

| Dolly | N | $ 115 |

| CamBam Plus software | N | $ 149 |

| MACH3 software | N | $ 159 |

| Laser Goggles | N | $ 82 |

| Steel Tray | N | $ 57 |

| DSP | N | $ 406 |

| Total | $3206 |

I have been working with the new Glowforge laser cutter for several weeks now and, thought it was a good time to post about it.

I first learned about the Glowforge project in July of 2015. A lower-cost laser cutter developed with a focus on usability sounded fantastic and, their early prototypes looked great. I have worked with a number of other laser cutters over the years, including units from Universal and Epilog (and, of course, the Blacktooth, which still needs a follow-up post). They remained impractical for studio use for various reasons.

My main concern about the Glowforge was their intent to use cloud-based software for operating it. If you have talked to me much or, read other things I have written, you may be aware that I am not a big fan of that sort of thing. Thanks to XOXO, I was able to talk to the developers and, they allayed my fear on that count somewhat. There are now also developers working on custom firmware for the machines at the OpenGlow project.

With shipping expected with a few months, I finally pre-ordered a Glowforge on the very last day of their campaign. In the great tradition of ambitious startups, it ended up taking a bit longer for them to actually ship production units …

So far, my Glowforge has proven worth the wait. It is easy to use and, I was up and running within an hour of its arrival. While I have found the learning curve so far fairly shallow, be aware that I already had quite a bit of experience with vector graphics, CNC, cutting machines, other laser cutters and, technology in general. The most common challenges I see people facing in the user forums are conceptual issues like not being familiar with creating vector images.

If you have browsed this site or seen my work elsewhere, you may be aware that I like to design origamic architecture pop up cards. The Glowforge has been great for quick prototyping experiments and, is even more suitable for small-scale production than I had hoped. Very granular control over the speed and power applied have allowed me to adjust for different types of paper stock to get both score lines and cuts without excessive charring or smoke damage.

Unlike CNC cutting machines, the laser doesn’t put any physical pressure on the paper. So, it is easier to work with finer details without as much risk of tearing.

Looking to experiment some with the level of detail possible when cutting paper with the Glowforge, I re-worked and adapted an old Celtic keypattern design I did long ago and, created a new Celtic spiral triskelion design. I wanted to do something useful with those. So, I turned them into kirigami bookmarks.

The Glowforge does not entirely obsolete CNC “craft” cutting machines like the Gazelle. There are still cases where that will continue to be the best choice, particularly for the paper art projects. I will likely post more about that at some point. One good example was an attempt to cut one of my Helical Heart cards. I use a stock with a particularly sumptuous finish for those. While the Glowforge did a fantastic job cutting the design, the heat of the laser bruised the stock along each cut – note the particularly pronounced damage on the inner point of the outermost heart. This stock has a particularly fragile finish, though and, I haven’t run into this with any other stock, yet.

[Updated] I pre-ordered my Glowforge with a filter unit that is intended to allow it to operate indoors without venting to the outside. Filtering laser exhaust is difficult and important to get right. At this point (May 2018), the filter units are still not shipping. In order to use my Glowforge, I built an acrylic panel with a vent hose connection that slots into the studio window.

Very early on, I discovered the Seklema mat from Johnson Plastics, which has helped quite a bit with holding down paper cutting work. A piece of wood or mat coated with repositionable adhesive also works in a pinch. The Celtic keypattern and triskeleon bookmarks I produced are excellent examples of the mat’s utility. Without it, small pieces would have been moved around during cutting by the Glowforge’s air assist, interfering with some of the cuts. With the mat, it goes without a hitch.

Neodymium magnets, wrapped in gaf tape flags for easier lifting, are also useful for holding down substrates to be cut or etched in the Glowforge. They attach easily to the steel grid tray.

The 40-watt CO2 laser in the Glowforge is capable of cutting more than paper, of course and, I would be hard-pressed to resist using it for other projects. In addition to a few things I am not ready yet to share, I produced a rubber stamp of one of my Celtic spiral patterns and, engraved some anodized aluminum flash drives. I am sure there will be much more of that sort of thing to come!

Glowforge has finally caught up on its domestic (U.S.A.) production and distribution. In fact, they have a number of their Pro units ready to ship immediately. They are offering a special deal on that limited number of units. If you are quick, you can score a $1500 discount while supporting me a little, too. Please use this link to order your own Glowforge Pro!